As I noted in the previous entry, the NYIFCC has completed

its survey of the top hundred films of the 1960s, adding to our list for the ‘50s

and the all-time list that we compile every ten years to coincide with the

Sight and Sound decennial poll. By fairly unanimous agreement we now proceed to

the 1940s.

However I would like to offer a couple of thoughts on the

1960s, a sort of cod-summation of what we “learned” from immersion in that

decade over two years. I have always thought of the 1950s as the pivotal decade

in American film, when the disconnect between the film industry and the mood of

the country became so extreme that it was the subtext for almost every

artistically significant movie released during the decade. It is

time when most of the tastemakers and the

economic and political leaders of the country are on the Eastern seaboard and

the West Coast is still somewhat isolated by the sheer size of the continent.

Hollywood, naturally solipsistic by temperament, is preoccupied with a series

of crises – the Blacklist, the rise of television, the fallout from the

Paramount consent decree, the aging of the studio heads, introduction of new

technologies like Cinemascope and 3-D, growth of independent production

companies and so on – while the seemingly bland Eisenhower era goes on around

it. The result is an underlying sense of tension, disorder, below the surface

of conventional genres, an unease that periodically erupts into violence. Think

of the central filmmakers of the decade – Fuller, Ray, Sirk, Anthony Mann – and

the work of the older filmmakers who hit new peaks like Ford (

The Searchers,

Wings of Eagles) and most of all, Hitchcock (

Vertigo,

Rear Window,

The Man Who Knew Too Much).

You could expand these lists with no trouble

at all, but I think you get the idea.

FROM THE '50S TO THE '60S IN A FEW EASY GUNSHOTS

By the 1960s the studios are becoming a non-issue, competing

smaller outfits like AIP have altered the playing field in interesting ways,

television has become the immovable object but also a source of talent and

income. The advent of lighter equipment and faster film stocks has spawned a ‘new

wave’ of filmmakers in Europe and they, in turn, fuel the American film

equivalent of the youth culture. Plus a lot of the newer filmmakers, having

trained in both live and filmed TV are used to working faster, cheaper and with

edgier material.

But what really sets the ‘60s apart, I think (and I only

realized this when I began assembling lists of films I needed to see or re-see)

is that it is the only decade in which you really have four basic generations

of filmmakers all working simultaneously: the old-timers who started out in the

silent era (Ford, Hawks, Hitchcock, among others), the theater-trained guys who

came in with the beginning of sound film, the writer-directors who emerged in

the ‘40s and the TV-trained guys from the ‘50s. The influx of film-school grads

doesn’t start until the ‘70s, but by then all but a tiny number of silent-film

veterans are dead or retired. My point is that for one decade you have an

institutional memory actually working in the field that goes back to the

earliest days of the medium; yes, Griffith and Murnau and Stroheim are dead,

but Ford and Walsh and Dwan are around to recall them.

I’m still uncertain what the overall impact of that

generational concatenation might be, but it’s something to think about. I

suspect that, ironically, the impact is greater for the film-school kids to

come because they spent a lot more time asking the silent vets questions and

looking at their films than working directors could spare. I could go on at great and frankly tedious length

about the ways in which the Internet and globalized media have changed this

equation again and again but you know all that stuff yourselves.

I must say that it will be a bit odd to shift gears and go

backwards in film history. The chronological juxtaposition of intensive

immersion in films of the ‘50s and ‘60s produced some interesting experiences

and ideas for me. Going backwards by twenty years should be an interesting

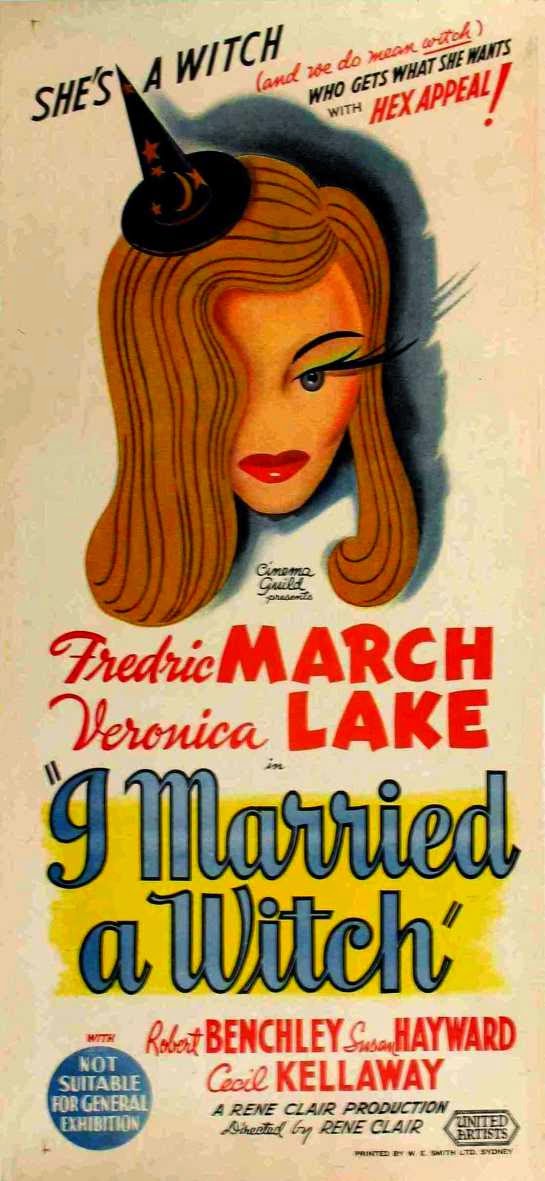

experience. Needless to say, there is plenty more to come. Last night Margo and I watched I Married a Witch, the 1942 Rene Clair comedy, and I'll have a few brief observations on that film in the next day or so.